| Español | Inglés | |

|---|---|---|

| Una Jarcha es una composición lingüística que formaba parte de las moaxajas, poemas en el dialecto hispanoárabe del pueblo mozárabe en la Península Ibérica. Las Jarchas son unos de los documentos escritos más antiguos que existen de la lengua romance. Los mozárabes formaban un grupo que integraba judíos. Así Los poemas fueron escritos por poetas árabes y judíos. Por eso contienen también partes en hebreo, en árabe y en mozárabe.

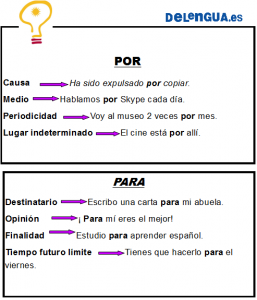

Generalmente las Jarchas fueron escritas por hombres, aunque están redactadas con la voz de una mujer contando sus problemas de amor a sus hermanas, amigas o a su madre. Se caracterizan estilísticamente por la abundancia de exclamaciones, interrogaciones y repeticiones, y el uso de un léxico sencillo con muchos diminutivos. Las cantigas son más o menos parecidas a la Jarchas: tienen la misma tradición popular y datan de la misma época. Hay cantigas de amigos galaico-portuguesas y cantigas villancicos castellanos. En los programas lingüísticos de la Escuela Delengua se puede aprender mucho sobre la historia de la lengua española. Nuestros profesores no sólo te enseñan a hablar español, también están formado para enseñar la literatura, la historia o el arte español. En los cursos de español de la Escuela Delengua te enviamos a un viaje por el mundo español. |

A “Jarcha” is a linguistic composition which took part of the “moaxajas”, poems in the hispanoarabic dialect, spokn by the mozarabian people in the Iberic Peninsula. Jarchas are one of most antigue written documents which extist of the Romanic language. Because the Mozarabians built one group together with the Jewish, the poems were written by arabic an jewish poets. Thats why they also contain parts in Hebrew, Arabic and Mozarabic.

The Jarchas in general were written for men. Although they are composed first voice of a woman who tells her problems of love to her sisters, friends or her mother. The mos obvious stylistisc chracteristics are abundances of exclamations, interrogations and repetitions, the use of simple lexicon and lots of diminishments. Similar to the “Jarchas”, more or less with the same popular tradition and with origen in the same time, there are the Galicien-Portuguese “Ballads for Friends” and the Castellan “Christmas-Songs”. In the linguistic programmes of the language school Escuela Delengua you can learn more about the history of the Spanish language. Our teachers not just show you how to speak Spanish, they are also educated to teach Spanish literature, history or art. In the Spanish programmes of the Escuela Delengua we show invite you to a journey through the Spanish world. |

For more information visit our website:

Search

Archives

-

Recent Posts

Tags

activities Alhambra Andalucía Andalusia Aprende español en España Aprende español en Granada Cine Español cinema cultura Cursos de espanol en Granada Cursos de español Cursos de español en España Cursos de lengua Cursos de lengua en España Cursos de lengua en Granada Delengua activities España español fiesta film flamenco Gramática Española / Spanish Grammar Granada hiking in the Sierra Nevada la lengua española Language courses language courses in Granada language courses in Spain learn Spanish learn Spanish in Granada Learn Spanish in Spain Pedro Almodóvar senderismo en la Sierra Nevada Sierra Nevada Spain spanish Spanish Courses Spanishcourses in Granada Spanish courses in Granada Spanish Courses in Spain Spanishcourses in Spain Spanish Grammar Spanish Language School the Spanish grammar the Spanish Language